Book Chapter with Jodi Keller-Kaye and Elizabeth Nix for “Baltimore Revisited: Social History for the 21st Century City”, forthcoming.

Book Release Party September 5th from 7-10pm at Red Emma’s Bookstore and cafe in Baltimore!

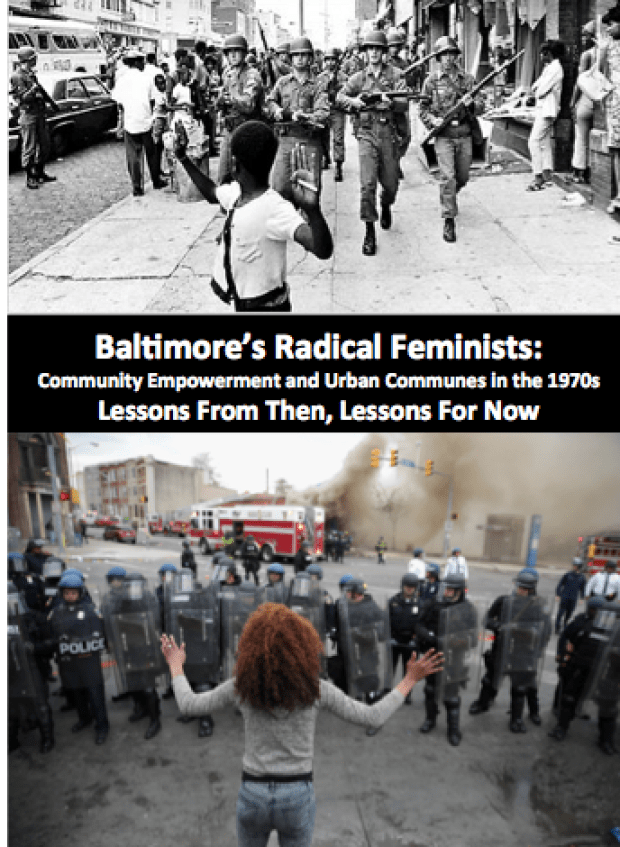

They paved paradise and put up… a CVS? One of the most memorable images to come out of the 2015 Freddie Gray protests in Baltimore was the news footage of the Pennsylvania Avenue CVS drugstore being burned and looted by protestors. While the mainstream media reported this as a misdirected attack against a respectable business, the protestors saw it as an opportunity to express their frustration with systemic race and class inequalities, symbolized by the corporate drug store chain. Months later, it was announced that the iconic gay nightspot, the Club Hippo, would be closing after 43 years of being the center of gay life in Baltimore. The Mount Vernon building, a long-time anchor of Baltimore’s gay community, where LGBT folks organized, marched in pride parades, met, and danced for over four decades, would be converted into a CVS pharmacy. What does it mean when CVS stores (read here as symbols of white corporate patriarchy) are placed at the centers of Baltimore neighborhoods where important community empowerment zones once occurred? Whether it’s Penn North or Mt. Vernon, when corporate capital moves in, communities have harder times controlling their own marketplaces and utilizing important empowerment strategies to keep their communities strong. In trying to more fully understand structural inequalities in Baltimore, it’s imperative to understand both the histories of communities who are disenfranchised and the models those communities used to foster consciousness-raising and political empowerment livable alternatives to structural inequality.

In the early 1970s, some young female academics moved to Baltimore to teach and to organize what they hoped would be the socialist feminist revolution, in addition to other revolutions they planned to organize. In the city, they found peace activists, feminist therapists, students and young wives eager to connect with women in the varied activities of second-wave feminism. Many of these newcomers gravitated to the cheap rents in the neighborhoods of Charles Village and Waverly, where they established institutions of a vibrant counter-culture: urban communes and collectives, women’s therapy groups, a feminist bookstore, a child-care center, a people’s free medical clinic, a food co-op, a coffee house, and Women: A Journal of Liberation, a national radical feminist publication which flourished for the next fourteen years. These radical and socialist feminists created a local community that was revolutionary then and many of those women remain politically active in Baltimore today.

This chapter is simultaneously a neighborhood history and a community history that examines the unique radical feminist collectives, communes and organizations in Charles Village and Waverly in the 1970s and the historic attempts made by these activists at creating a living model for social change. Using oral histories of the founders of Baltimore’s feminist and lesbian communes and collectives and the People’s Free Medical Clinic and articles from Women: A Journal of Liberation and the local press, we will argue that the socialist feminist ideology’s emphasis on creating labor economies outside of patriarchy encouraged Baltimore’s radical and socialist feminists to experiment in the fields of cooperative housing, publishing, healthcare and self-care and nurtured institutions that lasted for decades. We will situate these particular feminist communities in the larger national context of second-wave feminism and in radical and socialist feminist thought. Building on the work of Laurel Clark who examined the city’s 1970s lesbian community in her 2007 article “Beyond the Gay/Straight Split: Socialist Feminists in Baltimore,” we will examine how these communes and their political work came together, and how they shaped the city of Baltimore, then, and now. What worked, what didn’t, and what remains imperfect about the radical and socialist feminism that informed these urban communes and their politics? Given the deeply embedded structural inequalities of today’s Baltimore, we contemplate how these histories are reflected in a vibrant city capable of building radical and intersectional social movements and a collective consciousness based on the concept of equity.

Available at Amazon: Baltimore Revisited